O‘ahu’s only private snorkeling lagoon is also a wonderland for fish breeding.

52 The Mating Game Within the pool area of Aulani, a Disney Resort & Spa at Ko Olina, a saltwater lagoon glitters in the midmorning sun. Beneath its surface, hundreds of native tropical fish glide through a 3,800-square-foot reef designed to replicate natural marine habitats. Here, at what the property whimsically calls Rainbow Reef, guests swim and snorkel, immersed in a colorful tableau of angelfish, surgeonfish, and other reef species. While the reef offers guests a captivating experience, it also plays a vital role in Aulani’s sustainability efforts, fostering a thriving fishspawning habitat.

In 2016, Rainbow Reef joined a fishbreeding pilot project led by Rising Tide Conservation and Hawaiʻi Pacific University’s Oceanic Institute to test the viability of marine ornamental fish aquaculture, the practice of cultivating marine creatures for the aquarium industry. Though freshwater aquaculture is a common practice for reducing the impacts of wild fish collection, only a small percentage of marine species have been successfully reared through aquaculture to date. The success of the pilot project hinged on two critical stages: the systematic harvesting of fertilized fish eggs by Rainbow Reef and other aquarium partners, and the raising of the embryos into juvenile fish in the Oceanic Institute’s nursery. Early in the project, Rainbow Reef emerged as an ideal egg-harvesting partner thanks to its carefully managed ecosystem and abundant egg production.

“Our fish are so happy and comfortable in the lagoon that they don’t really have to think about anything else—they’re just busy producing eggs every day,” says Rafael Jacinto, the animal and water sciences operations manager at Aulani. “We’re great at keeping the parent fish healthy, and the nursery team focuses on the rest—food culture, microalgae, feeding larval fish—which can be major roadblocks in aquaculture. Everybody is doing the best that they can.”

Jacinto attributes the fish’s prolific spawning to the meticulous care the Animal Programs staff takes in maintaining a harmonious ecosystem. Additionally, the strategic mix of fish species—mostly herbivores with a few predatory fish, modeled after Hawaiʻi’s near-shore ocean environment—plays a key role in ensuring the health and productivity of its inhabitants. According to Spencer Davis, a senior research associate in the Marine Finfish Aquaculture Program at Oceanic Institute, Rainbow Reef ’s team was integral in establishing the project’s proof of concept. The shared passion is there too. “There’s a synergy that stems from our crews getting equally excited about what each other was doing,” Davis says.

Such teamwork makes the dream work. Not only was Rainbow Reef the first of the collaborating partners to confirm the feasibility of their egg-collection setup, the pilot project led to the first recorded captive breeding of the Hawaiian cleaner wrasse, a bright blue and yellow fish, and the playful Potter’s angelfish, both endemic to Hawaiʻi, as well as the kīkākapu (raccoon butterflyfish) and lauwiliwilinukunuku‘oi‘oi (longnose butterflyfish), two of Hawaiʻi’s native fish species.

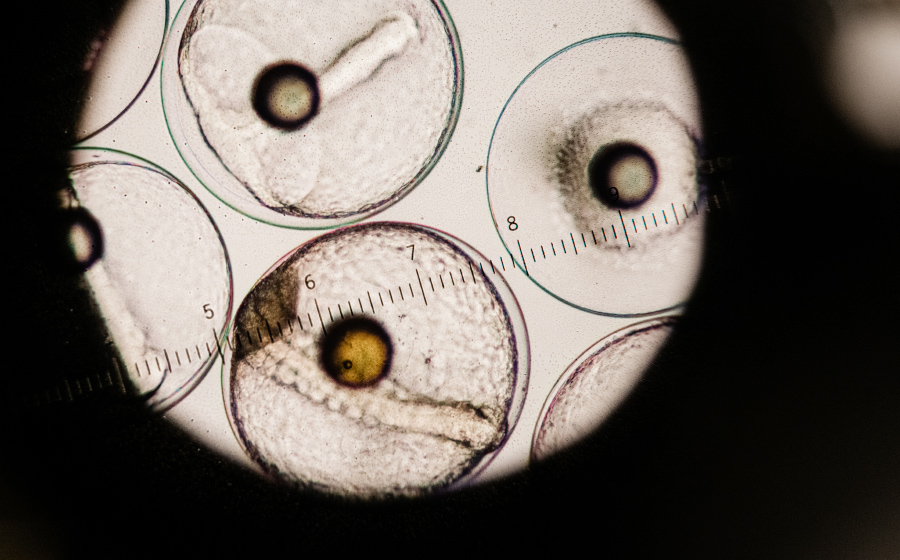

Newly spawned fish eggs are captured in nylon mesh jars at various spots around Rainbow Reef. A float test is done to separate the viable eggs from the nonviable ones (the viable eggs will float), then the embryonic fish are bagged in oxygenated water for transport to the nursery. The Rainbow Reef team regularly logs egg-production data as a reliable indicator of the health of the marine life. “If there’s a big drop in egg counts on any given day, we’re checking to see if a change in diet, habitat, or other factor could be causing an imbalance,” Jacinto says. As of 2025, Rainbow Reef is a regular donor in support of Oceanic Institute’s ongoing aquaculture efforts, generating anywhere from 30,000 to more than 100,000 viable eggs per collection.

At Oceanic Institute’s biosecure facility in Waimānalo, the fish eggs are counted, disinfected in a diluted hydrogen peroxide bath, and then placed into 1,000-liter larval-rearing tanks. The most labor-intensive part of egg rearing is farming the plankton for live feeds, Davis explains. In addition to ensuring each species receives the appropriate food, the scientists must provide the fish with larger varietals of plankton as they mature. “These are live animals, so there are no days off,” he adds. “You have to physically be here to care for them for more than eight hours a day.” When the fish reach juvenile stage—in one to three months, depending on the species—they can be transitioned to an artificial diet in pellet form.

At this stage, the cultivated fish are sent to Oceanic Institute’s partners, such as state or federal agencies, public aquariums, fish wholesalers and retailers, and conservation groups. Last fall, Oceanic Institute and Rainbow Reef worked with the Hawaiʻi State Department of Land and Natural Resources to release 300 captive-bred juvenile yellow tang in the coastal waters around O‘ahu, including those fronting Aulani. The milestone event marked Hawaiʻi’s first documented release of fish aimed at ecosystem restoration, as opposed to population increase.

Sediment runoff and toxic substances, like sunscreen containing oxybenzone, contribute to the development of invasive turf algae, which smothers coral. Yellow tang graze on the turf algae to help keep it at bay. “When we first opened Rainbow Reef, we started with around 300 yellow tangs in the lagoon,” Jacinto recalls. “During that one day, we were able to return roughly the same number of yellow tangs back to the ocean. That’s pretty special.”

More about Rainbow Reef at Aulani

Aulani, a Disney Resort & Spa

92-1185 Aliinui Dr, Kapolei, HI 96707

Call: (866) 443-4763

Visit: disneyaulani.com